In the old days, writers sharpened pencils, checked the mail, experimented with melismatic renditions of “I’m a Lumberjack, and I’m Okay,” polished the piano (the rich writers, I mean) and so on. Classic avoidance behavior, right? Anything’s better than actually getting down to the hard business of writing.

In the old days, writers sharpened pencils, checked the mail, experimented with melismatic renditions of “I’m a Lumberjack, and I’m Okay,” polished the piano (the rich writers, I mean) and so on. Classic avoidance behavior, right? Anything’s better than actually getting down to the hard business of writing.

Maybe not. Or at least maybe not entirely. I’m not the first to suggest that all the screwing around may well be a vital part of the creative process. Having exhausted the possibilities of melodically ornamenting classic songs, you return to your manuscript and, hallelujah, that recalcitrant plot problem is resolved. Like magic, perhaps one of your characters supplies just the snatch of dialogue needed to precipitate the missing dramatic profluence.

Creative foreplay. Simply getting away from the book for a relaxing stroll can be enough to tickle the Muse. Some part of “avoidance behavior,” in fact might better be described instead as creative foreplay.

When avoidance behavior isn’t really. Sharpening pencils, listening to music, making a few phone calls, gazing at the nice day outside… You’re really working, eh? It’s like lateral thinking, or deliberately not thinking about a word that’s on the tip of your tongue.

But the art of productive screwing around has become much more difficult, in this modern age. You can sharpen all the pencils in the house, but, once they’re sharp, that’s an end to the matter. True, you can go on from there to polishing the furniture, but again, that gambit soon plays itself out. In any case, these are essentially restful, mindless activities, conducive to behind-the-scenes rumination and synthesis. In a way, you can do these things and still, on some preconscious level, be productively involved in your book. The difference today is we’ve got the Internet. Google, Amazon, personal blogs and websites, our friends’ blogs and websites, Facebook, Twitter, games, magazines, books, news, commentary, Google Earth… We have the collective memory and, increasingly, the collective mind-in process lurking right behind that page of manuscript—the one that’s proving such a bother and, boy, you sure could use a break, eh?

Dopamine addiction. So the first point is this: There’s a ton of stuff to do rather than work, and much of it is pretty neat. Unlike with pencils and furniture, you’re never going to come to the end of the distractions at hand. Many of them even come loaded with nice little hits of dopamine.

Secondly, for the most part these distractions aren’t entirely mindless in the way sharpening pencils can be. They engage you. And they’re infested with hyperlinks and whatnot that hijack you, pointing every which way, diffusing your attention and creative energies. Look at this! And this! Whoa, what about that? This effect then becomes multiplied exponentially by the fact you can flip effortlessly between Arts & Letters Daily, Facebook, e-mail, Twitter, a new lecture series, and even notes towards some other novel, one that’s easier to write.

Or you can compose another blog item, like this one, the longer the better, because then you might avoid real writing till lunchtime, and then… Well, a man’s got to eat, eh?

Advanced avoidance behavior: Sharpen pencils somewhere new and exciting (and, if you’re really serious about this, beyond the reach of the Internet, should such a place remain).

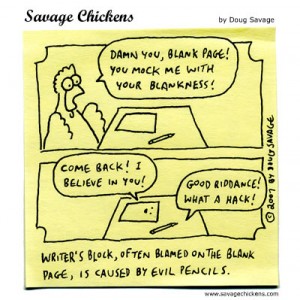

Thanks to Doug Savage for permission to use the Savage Chickens cartoon.

Another take on related matters, two years on: http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/02/upside-of-distraction/?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20130205.