This week we join Jack Shackaway on an interesting trip through Bangkok traffic. His trusty old typewriter, which he’s meant to get rid of for years, proves useful.

- HAPPY DAYS. Soon everybody in the country will have a couple of Benzes, not to mention pots full of chickens. Dearie me, yes; the race to NIC-hood (Newly Industrialized Country status, for those of you from outer space) is bringing on a New Day for us all. Now if only we Bangkokwallahs also had somewhere to drive our Benzes, and some air to breathe, especially when we can’t be sitting in some fine car with the air-conditioner going flat out.

- ANOTHER TYPICAL WEEK. Five Aussies found dead of drug overdoses in guesthouse rooms. Two Germans in the same shape in Pattaya. One Swede dead of alcohol poisoning. Twelve Nigerians busted for possession of heroin at Don Muang Airport. Various ‘dark influences’ removed 30,000 acres of pesky forest and paved over thirty miles of sandy tropical beach. Another 2% of the country was covered in golf courses. Seven powerful businessmen, victims of ‘business conflicts,’ were found dead of lead poisoning behind the wheels of their Benzes, except one of them who was driving a Volvo. Millions of children in Bangkok, meanwhile, continued to flirt with lead poisoning just by breathing the rich city air.

In Bangkok laborers made ninety baht a day, if they were lucky. A freelance writer was even luckier than that, sometimes.

Just think — ninety baht a day, and a Big Mac cost fifty baht. A bottle of beer in a five-star hotel could go for 110 baht. A little tiny Camembert cheese was almost 100 baht; these laborers had be grateful they didn’t like cheese, though many freelance writers had no such grounds for gratitude. My girlfriend Mu looked at me like I was crazy if I bought one Camembert every three months.

Bus fares were going up again, I heard, and I guess I could handle that. Though many could not. The people who wanted to build the Skytrain said they would have to charge twenty baht basic. Sure, and you were making ninety baht a day or maybe less, and you could spend forty baht a day just getting to and from work. No problem.

Meanwhile you got all these Mercedes-Benzes and BMWs stacked up at the traffic lights; it was almost an embarrassment to be seen in a Toyota Crown or a Volvo. And you could buy a Benz for a few million baht, since there was only 600 percent duty on one of these nice pieces of engineering. Of course if you were rich you didn’t have to pay this duty; there were ways around it, and some of these ways came up across the Malaysian border. And a few of the Benzes, I saw, now had gold hood ornaments; I guess since there were so many Benzes around these days it was no special distinction to be seen in one unless it was 24-carat. At ninety baht a day you worked for some time to save up for such a car, even if you cut corners on your food expenses and such-like. Even if you made more than ninety baht a day, as I did sometimes.

These were some of the thoughts that were occupying me, this hot day in July. I had spent all the money from the gunman stories, not to mention the piece I did on that deputy minister Wrong-Way Willie put me onto, the one who had interests in whorehouses all over the south. That one had created a little stir. I was surprised the paper used it. Anyhow, the money from that was long since gone. Though now I had had a new score to tide things over.

And what the hell, I was thinking. Bangkok was home. Even when a guy was broke half the time and had no Benz, not even a Toyota. Even with a hangover. Even though I was trying to kick tobacco again and wasn’t finding any part of existence entirely comfortable. Even though my woman, Mu, was not altogether happy with me right at the moment. Even though there were men with guns somewhere out there and they were looking for me. Of course I didn’t know about that part of it at the time.

This day I was riding along in a taxi with my old Royal typewriter on my lap; I was going to sell it to a shop down in Chinatown. I didn’t like to part with this classic machine, but just recently I had gone hi-tech. I had bought a nice Taiwanese IBM computer clone and a pirate word-processing program that turned me into a writing factory compared to what I had been able to do with the antique Royal, and which besides gave me lots more time for drinking beer and suchlike. So I was thinking life could have been worse.

Only a couple of weeks before that, I had got back from a trip to Burma, where I had to see about getting another visa so I could live in Thailand some more, and Burma did me a favor by having something like a revolution right in the middle of my vacation-cum-visa run. Now your average person is often not happy to find revolutions in countries he visits. And I understand this attitude. But your average person is not a freelance journalist with a chronic shortage of good things to write about. Which is something I am. And right then Burma stories were selling like hotcakes, even my stories.

So things were more than just okay, and I was smoking a big cheroot with the window open because my driver was not so keen on big cigars. What my driver was keen on was “rive shows,” and he thought I should be keen on them too, never mind I kept telling him to for Christ’s sake shut up and drive, I was an Old Hand and I didn’t let taxi drivers take me to see live shows.

“Good. Is good. Lookee, lookee only. Man-woman show. Fucking.”

But that was Bangkok these days. Everybody out to make a buck, it was boom times, NIC-hood in the air. Thailand was going to be a Newly Industrialized Country. One of the Five Tigers of Asia. The whole country was one big feeding frenzy, with condos being built on top of condos; the skyline was a tangle of building cranes, and people were slapping up hotels or else department stores anywhere other people had forgotten to put condos. You added the banks and the tour agencies, and you got the whole show paved over with glitz. Tourists carried in money by the plane-load, with 6,000,000 of these public benefactors expected that year. And Thailand had stopped lobbing artillery shells across the border at Laos, and had taken to bombing them with baht instead, it being more cost effective to use money I guess, though I have never understood economics. Turn the Southeast Asian battlefield into a marketplace; this was the new plan. They had sold the Thai forests already, so now we had Burma to supply teak for the nice houses for the nice Thai people who were running this market that was no longer a battlefield, except maybe for some little problems, like where for example the Burmese were wiping out the Kareni. Hey, it wasn’t just because they were a bunch of dirty separatists; no, they were also messing with the traffic in logs across the border, and anybody could tell you that you didn’t want to screw around with Commerce. And you didn’t hear much from the communist insurgents in the south anymore; it was hard to sell communism when there was the scent of money to be had in the air and, who knows, a car in every garage besides and a couple hundred more air-conditioned shopping malls to amble around in. What did your average Marx or Lenin know about any of that? I ask you.

The TV and newspapers were full of taskforces and master plans, not to mention working groups and crackdowns. Everybody was having a hell of a time, and it was projects here and projects there, and my goodness, wasn’t it a shame the way the shit settled all over your Benz in this city? It was this pollution; somebody should do something, maybe set up a taskforce. It wasn’t just the government and big business, either; school boards and who knows probably even noodle vendors had to have their master plans and taskforces these days, or they weren’t up to date, which was one measure of anything’s value these days, whether it was up to date or not. These were exciting times. Everyone wanted a piece of the action, including my driver this day I was telling you about.

“You want lady?” he asked me.

“Shut up and drive.”

“You want rubies? Sapphires?”

“Just drive.”

“Snake farm?”

I was thinking I should get out and walk; it was as fast anyhow, given the traffic. Even the motorcycles had a hard time going anywhere; half a dozen of them were swarming around my taxi right then, waiting for an opening. Some of them carried two passengers, some of them with girlfriends modestly riding side-saddle so I couldn’t look up their skirts. It was better, you had to think, they ran the considerable risk of falling off the bike and creaming themselves than some stranger got to look up their skirts. There was one with a whole family of four on it — momma and poppa and two toddlers sandwiched in between.

I could hear the sound of voices through the window: “You! You!” This was what Thais of a certain class did when they noticed a foreigner such as myself and they had some time to kill. I ignored them, but they went on in a similar vein. “You! You!” they said. I guessed they didn’t mean any harm, though it smacked more than somewhat of baiting the farang.

Just for something to do, I timed the light, and I saw that we had been sitting there already for ten minutes. I held the computerized traffic lights, those early signs of NIC-hood, responsible for this inconvenience. It was all only show, anyhow, like a lot of other things I saw around me. In fact, they had traffic policemen everywhere you looked, supplementing the hi-tech light system probably according to some master plan. Like there wasn’t enough noise in this city as it was, Bangkok police kept the traffic moving by blowing whistles at it and waving furiously. When they wanted a lane to come to a halt, they stopped blowing and turned their backs on it, which took some courage, I had to admit. It was like pulling off a veronica with around fifty giant bulls bearing down on you all at the same time. Personally, I would award any one of these officers a couple of ears and a tail.

This morning the radio news was purring along with the government line, so happy with its statistics. The only news on Thai radio was business news and the only business news was good news, said the government. In the middle of this the announcer informed us this year there were thirty percent more “units” of automobile sold than last year, and wasn’t that something? We were all getting rich. Never mind it looked as though the whole city was going to seize up tight. There were too many cars already, and one morning soon we would get up and think about going to work, and everybody would suddenly notice we couldn’t go forward and we couldn’t go backward either, so we would get out of our cars and walk; and where was the NIC-hood when nothing in the place moved unless it walked? But it is hard to ask questions like these during a feeding frenzy because everybody is generally quite busy, and they don’t listen.

“Jesus Christ!” I hollered, meaning to signal some alarm to the driver.

He had found an opening in the traffic and we were out on the expressway, gamboling along like a colt let out to pasture in the spring. The thing was, at the same time he took this opportunity to cut loose, my driver saw a temple, and I had to think this temple meant something special to him, because he took his hands off the wheel and brought them together up to his forehead in what the locals call a wai, he wanted to show his respect, and we veered off across four lanes of traffic, which inspired much spirited honking of horns all around and lots of stylish swerving of vehicles to make way. By comparison, revolutions in Burma left me feeling quite relaxed.

I forgot to mention that my driver was no ordinary driver, and the taxi was no ordinary taxi. In this age of approaching NIC-hood not to mention gridlock, Bangkok cabbies were getting nervier and nervier about asking an arm and a leg to venture into traffic at all, and it seemed the process of getting a fair price was starting to take a disproportionate amount of my time. So this day I had turned away from four or five cabs in disgust, and almost thought about getting on a bus, never mind the heat and the fact there was no place to sit on the buses anymore; they started their routes with all the seats already occupied, I don’t know how they did it. I was looking around for one of these public services when I heard a car-horn croak at me and then a person also croaked “You! You!” and I looked and it was a Mercedes-Benz, about 1957 vintage, body-work done with a ballpeen hammer, bottle-green paint slapped on by hand. The driver was older than the car, probably pushing ninety-five or so, and it looked like somebody had also worked him over with a ballpeen hammer some time in the past, though he wasn’t painted green.

“Where you go?” this individual asked me. “I have car.” The old man climbed out of the Benz, probably checking to see if he could still stand up on his own, and he wanted to know which hotel I was staying in. The condition I was in, I was wishing he wouldn’t mess with my head this way; I got the crazy idea the whole planet was on tilt. This geezer grinned at me and listed to one side. He toppled over a bit, took a crabwise hop or two to catch up with himself, and then stepped back to his original position. He went through the whole routine once more, and then he asked me again, “Where you go?”

I told him where I was going, and right away I said, “Fifty baht, okay?”

“Okay,” he answered me, just like that, and I couldn’t believe that was all there was to it.

And I was right. He got in the front again and slammed his door. I jumped in the back and my door also shut after I slammed it two or three times. You could say car and driver were about equally clapped out. Where you got the taxi lurching, the old man would go into a spasm: one shoulder would convulse and his head would twist around till he was looking into the back seat. Where the car shuddered, the driver trembled as though he had the DTs, and he made funny wittering noises. First I thought it was the valves.

But now we were out on the highway, out of the worst of the traffic. It took some time to get the car up to thirty-five miles per hour, this machine being no dragster. But I was grateful we were moving at all, because the air-conditioner was busted and now there was a breeze through the crack in the window. I closed my eyes and thought nice thoughts about the Burma articles and about money, and I was almost drifting off to sleep when I heard what sounded like a death rattle from the front seat and my eyes popped open. We were doing about forty miles per hour now, thanks to a gentle downgrade we had come upon, and we were weaving from lane to lane in a way that made me think Bangkok buses weren’t such a bad thing after all. Probably the driver was trying to guess which side the much faster traffic from behind was going to pass on.

There was another death rattle. The driver had one of his convulsions and he twisted around to look into the back seat. “You want crocodile farm?”

“Keep your eyes on the road, okay?” I suggested. Actually, I kind of screamed it. “You crazy bastard!” I added.

The blare of horns prevented the crazy bastard from hearing this, however. He swerved into the next lane just as a gaily decorated ten-wheeler truck came up on us and shot by at somewhere around the speed of sound. Then he whipped the car back into the lane we had left before, causing a Toyota Crown to go into a squealing four-wheel drift. Trembling and twitching, grinning and drooling, the driver continued his exploration of all the four lanes while I thought about this and that, mostly about how I didn’t really want to go where I was trying to go anyway; and why hadn’t I stayed at home? This was a good day to stay at home. Or maybe to go wait for happy hour at Shaky Jake’s. The Benz was doing all of forty-five miles per hour by this time, and there was an alarming chatter coming from somewhere up under the hood.

“You want rive show?”

“I don’t want anything! Don’t you understand? Nothing! I want nothing. Just drive.” I slid down on my seat, out of sight of the road and the traffic, telling myself not to get so excited. But it was only that I didn’t want to die right then, not with money in my pocket and my hangover almost cleared up. You know how it is.

There was silence from the front seat. Then, in surprised and respectful tones, he said, “You want Buddha?”

I got out the pipe I had brought along for emergencies. I stuffed it full of nice dark tobacco and lit up, puffing hard to get it going well, laying down a cloud of smoke that sent the driver into spasms. I had the idea he was trying to say something to me, but he couldn’t stop gasping and wheezing long enough to get it out. I puffed some more, but he had managed to get his window wide open, which mostly cleared the front seat of smoke. Possibly he still had smoke in his eyes, however, because he suddenly cut off a Volvo tour bus coming up from behind like the Cannonball Express, and I couldn’t believe he meant to do that. Those tour buses don’t ever lose at chicken. It’s a point of honor with them.

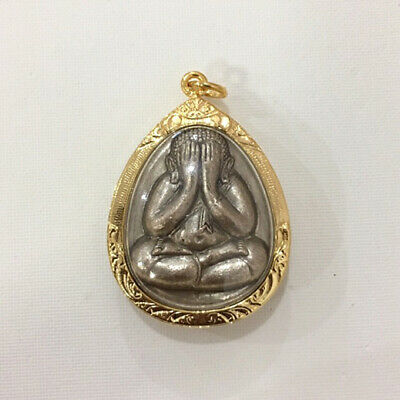

I fingered the amulet that hung on a silver chain around my neck. My girlfriend Mu had given me the thing as protection against injury. A doodad from some temple upcountry. Big magic. GIs on R&R from Vietnam liked to pick these things up in the old days, I hear, and some of those boys, anyway, got back Stateside in one piece. Who knows? Maybe it was because of amulets. This one was a tiny silver Buddha-like figure with its hands over its eyes. What it wouldn’t look at couldn’t hurt it. That’s what I would tell Mu, anyway — just like the Thai public, who were getting railroaded by business interests into selling off their forests and their beaches and their children, and not saying a thing about it. Mu didn’t laugh. You had to take your magic charm seriously, if you wanted it to work for you. Mine had four extra hands, actually, the deluxe model, and they covered four other openings I guessed your miscellaneous slings and arrows of outrageous fortune might look for.

Mu’s world was full of spirits and magic. She didn’t like it when I razzed her about this, either. And I couldn’t say anything negative about Thailand. Anything Thai was okay, as she explained to me again and again, because it is the Thai Way. And I knew dick about the Thai Way, was the unspoken corollary to this proposition, so what could I say?

This woman Mu was not a standard model of Thai woman, in some ways, though in other ways she was, through and through; and she was as a consequence twice as hard to fathom as your average Western woman, who was in my experience already pretty hard to make out.

We came off the expressway, and we were almost there. Now I would be able to flog my Royal and then try to hit happy hour at Shaky Jake’s. Only we were in heavy traffic again. The air was not moving and the heat was making me sweat into my shorts and my hangover was coming back. It was so bad I couldn’t even smoke my pipe. We were stopped at a light, and the exhaust fumes were settling on my spirits like a pall. This was giving me a headache, as the motorcycles percolated through the boiling traffic to condense up front, up by the light. Some of the drivers were honking horns probably for practice, since nothing was going anywhere, except for the steady trickle of motorcycles. I was thinking for the hundredth time I should get a motorcycle, it was the only way to get around in Bangkok these days, except I knew I would kill myself the first time I forgot I had had a few beers and tried popping wheelies on Sukhumvit Road. I was also thinking about Mu, and I wondered whether I should bring her some fruit, after I got away from Jake’s, maybe a great big durian.

Then I heard “You! You!” from just outside the window again, the traditional baiting of the foreigner. Some jerks on a bike. I tried to ignore them, practicing my jai yen yen for Mu, learning the Thai Way, maintaining my cool like I was a frigging saint or somebody, when there was a sharp rap on the glass beside my head.

“What the …?” I turned my head to give them this short lesson in colloquial English I had in mind, only I found my glare being returned by the muzzle of an automatic pistol, enormous through the glass at a range of eighteen inches.

I heard “You” again, repeated more softly this time and furthermore punctuated by the bark of a gun. My head snapped back as soon as the shooting started, and I twisted around to hit the seat, sliding down onto the floor with the typewriter on top of me. The pistol barked twice more.

The cabbie first screamed like a woman. Then he started making funny noises; you would have probably thought somebody was tickling a sick goat in the front seat, if you didn’t know different. I could have wished he would clam up, though, there being enough turmoil as it was. I was wedged down on the floor of the back seat, my eyes still shut tight against the blast and the glass and the prospect of about one second’s life left for the living, which was less than I had planned on up to this time. My ribs hurt like a son of a bitch, though, which was reassuring, since it seemed to argue that I was not dead after all. What it was, the corner of the typewriter was digging into my chest trying to pass itself off as a bullet wound.

Suddenly I noticed I wanted to do some screaming myself. But all I did was holler “My eyes! My eyes!” Why I did this thing, there was this searing pain in my eyes, and a sick feeling in my guts as I reached up to check for blood, for bits of sharp glass imbedded in flesh. All I could find, however, was some liquid that was only tears and this gritty substance, which I rubbed at cautiously. One eye cleared enough to see, and I put my fingers to my nose and sniffed. Pipe ashes, cold ones at that. Stung like a bastard, you got pipe dottle in your eyes. Lots better than glass, mind you. Or bullets. My pipe, though, was no more. I guess the first bullet caught it as I threw myself back, smashing the bowl, exploding dottle and bits of briar all over the inside of the car. The second or third shot ricocheted off the underside of my typewriter. There was this be-dwaanggg, just like in the Wyatt Earp TV shows. It didn’t look like a mortal wound, though. Those old Royals were built to last.

I started to laugh, now. This laugh was too high-pitched to qualify as a chuckle, and it sounded weird even to me, as though I were listening to somebody else, and this person maybe wasn’t as entirely happy as he would have you believe. By the time I pushed the typewriter up onto the seat and wriggled out of the back seat and got out on the pavement, though, I realized that I was okay, just about as good as new and possibly better, since I could detect no trace of the hangover at all. It could be adrenaline is a cure for hangovers. There was already a crowd of people having a good gawk at this crazy farang laughing away at a taxi full of bullet-holes.

It was like a miracle or something, I was thinking, as I fingered my amulet some more. I also thought about that article I sold after Mu gave me this thing — the one where I talked about the history of these items. “Many Thais actually believe these charms protect them from bullets and knives,” I had written. “I don’t think I care to test that claim.” This was still true; I didn’t care to test it.

Traffic was now moving, to the extent Bangkok traffic ever moved, and behind the cab there was the blare of horns. We were getting cars, tuk-tuks, motorcycles, and buses turning and making their way around, accelerating past with angry looks at me — who was this klutz standing in the road with a shot-up taxi? They couldn’t glare at the driver; he was still out of sight in the front seat praying to various agencies, most likely, and imitating a sick goat.

.

Next week Jack is asked to make a contribution to the policemen’s Tea & Biscuit Fund.