Back before New Year’s, I posted a couple of blogs that meant to ease writers into the process of writing, rather than only talking about writing. I was subsequently sidetracked by the need to outline some flaws in the Scheme of Things, but now I’m back into this solipsistic writing workshop. But all we’ve discussed so far is only part of the story. Now I’m going to talk about The Muse Effect.

“Wherever do you find the discipline?” they ask. “Doesn’t writing take an awful lot of discipline?”

“Wherever do you find the discipline?” they ask. “Doesn’t writing take an awful lot of discipline?”

In my experience, that’s the most common question people ask, immediately after you are introduced to them as a writer. (Actually, it’s only the second most common. The most common is “Can you make a living at it?” this question being expressed in tones of wonder. And well they might. Wonder, that is.)

Creative writing does require discipline. Just what, however, does this proposition really mean? Is it no more than a matter of chaining yourself to a computer?

Here’s where the discipline comes in, I believe:

1. First, you have to be willing to bang your head against the story for days, even weeks, even when you can’t really see the story and have no idea where it’s all going. In short, you have to be prepared to behave like a nutcase for a time, at least at the outset.

2. Once the story is up and running, you’ve got to have the discipline (and the financial resources) to resist all the demands on your time and attention that threaten to derail the project. Once derailed, you’ve got to go back to Phase 1, except this time it should be easier, since you’ve already proved to yourself it can be done. In my experience, it can take just as many days as it did the first time (usually five to seven), but it’s easier to have confidence that all the head-banging will prove fruitful.

To write fiction, you’ve got to become obsessed, to some extent, by the problem of the story. With non-fiction, on the other hand, the lumber is generally already there. With fiction, you really need incentive to keep going even when you can’t see where you’re going or, sometimes, why.

This is where The Muse Effect kicks in.

THE MUSE WEARS BLACK LEATHER

Contrary to popular belief, writing fiction can be easy. Properly undertaken, it hardly requires any self-discipline at all.

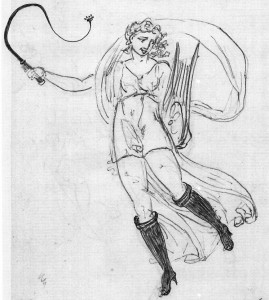

Most people think of the Muse as a sweet young thing. She (he/it, I suppose, depending on the writer’s proclivities) comes draped in lengths of diaphanous cotton and smelling of soap, an apparition in soft light who gently massages one’s creative faculty, smiling and whispering excellent suggestions in one’s ear. But that’s malarkey. Properly courted, in fact, she comes stalking at you in black leather boots and carrying a whip. The Muse is a disciplinarian bitch.

The hard part is attracting the Muse in the first place (always supposing you really want to mess up your domestic life in this way). But once you do, writing can be more like demonic possession than work. When the spirit seizes you, like it or not, you write. Something outside or beyond you begins to direct proceedings, dictating additions and deletions, legislating revisions. The stories start to appear as though by magic. In this state, it takes no self-discipline whatsoever to write.

Writers talk, for example, about the point at which a story can take on a life of its own, where the characters start saying and doing things that seem just right, somehow, but which nevertheless were no part of the writer’s conscious design. Rather than working from any preconceived plan, enjoying instead the surprise of real discovery, the writer seems at this juncture to be merely an amanuensis for some higher inspiration. Indeed, it is at times such as these that the activity of writing is most satisfying, almost magical. This is the Muse at work. (I speak from the perspective of the writer, of course; in my own case, some readers may wonder where all this magic, where all of these autonomous, practically flesh-and-blood characters have got to in my stories. Never mind; subjectively the experience is still a magical one.)

Here’s the thing: Ninety-nine percent of the people who claim they’re going to get around to writing a story one day never will. And that’s at least partly because they never reach the stage where they have an affair with the Muse. From time to time most of us feel certain vague urges, an almost erotic hungering to create. But don’t mistake this for the real thing. Sitting down with nothing but one of these spurious rushes of creativity, only to be faced then with the enigma of the blank page, you’ll be lucky if you get beyond a single pointless paragraph. The infinite possibility represented by that expanse of featureless paper can quickly drain any passing creative lust.

It is at this point that most people quit, usually for the rest of their lives. How can it be that one’s very soul is swollen with the passion to create, inflamed with all this inchoate meaning and beauty, yet nothing comes? In fact, this is the moment of truth. The people who go through the rest of their lives announcing their intention to write a novel, just as soon as they find the time to sit down and await inspiration—these are the ones who feel the urge pass for the moment, then shrug and turn on the TV. They decide to wait till they’re “in the mood.”

Those who recognize the necessity of getting something—anything—down on paper, on the other hand, stand a chance of becoming a writer. The first hurdle any writer faces is that of actually starting something.

Those who recognize the necessity of getting something—anything—down on paper, on the other hand, stand a chance of becoming a writer. The first hurdle any writer faces is that of actually starting something.

It might help to remember this: It’s a mistake to think you must know what you’re going to write before you write it. You always know more than you think you do, for one thing. The trick lies in coaxing it out. Writing is a process of communing with the page. A story emerges through the evolution of the text as a critical dialogue between the writer and that text as it emerges. The essential thing, initially, is to begin the dialogue by getting something down in writing. It doesn’t matter what; anything will do so long as it starts the process. Don’t think. Write. (At this point the Zen writing master hits you with a big stick.)

But this is only the beginning. So far you are on your own, real inspiration yet to come, the gods willing. What may follow is days and days of long hours spent in frustration, doubt, and despair at ever seeing the story come to life. You suspect that the story is not really a story, that you aren’t a writer. You think of a hundred more constructive ways to spend your time. You flail about, to all appearances a total loony. This is where discipline is truly needed, although “pathological orneriness” may be closer to the mark. The whole procedure can seem just as creative and almost as enjoyable as banging your head against a wall. But that’s as it should be. You can’t simply wait for the Muse. You’ve got to go after her, offering whatever tribute she demands, seducing her with much earnest head-banging and tearing of hair.

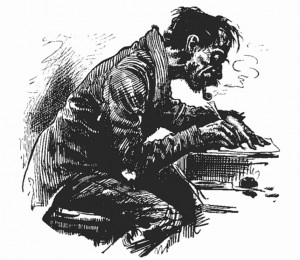

Then one day you get up and, right in the middle of your morning shower, you find yourself abruptly mugged by inspiration, dragged by the ear into your study, dripping suds all the way to your computer. By lunchtime you may be given time to rinse off before eating. Lunch itself will as likely as not be interrupted by an idea or two that demand noting down before they evaporate. And this state carries over from day to day. You now embarrass yourself by making notes in the middle of dinner parties, scribbling away in taxis, wondering whether your lover would mind if you interrupted proceedings, just for a moment, to record a sudden notion that has occurred at this most awkward of times. Everywhere you go, bits of everyday experience start to take on new significance, as you find yourself interpreting much of what you perceive in terms of story material.

Well and properly seduced, now, the Muse obliges by making your work even easier. When you awake in the morning, so long as you can get to your computer before too many distractions arise, the story that finally seemed so intractable the day before pours out onto the page by some process akin to automatic writing. As a Graham Greene character, a writer, once put it, this morning gift of the Muse is more like remembering than actually creating something new. You find that some part of your mind has been busy all night, and the story has worked itself out even as you slept. With any luck, then, the Muse welcomes you in the morning with that day’s episodes ready for dictation.

This state is the ultimate reward for many writers. (I say nothing of Hollywood contracts and suchlike.) It is not, however, considered a total gas by family and employers and other people with claims on your time.

And, having once achieved union with the Muse, this is by no means necessarily a permanent arrangement. Most writers will still encounter a problem of discipline, notably in the conflict between the demands and temptations of bread-and-butter work (in my own case it was as a professional writer and editor of non-fiction), and the desire to develop whatever talents they have as fiction writers.

Writing short stories and novels requires assiduous courtship of the Muse. This campaign, however, is constantly interfered with by the seductive promise of almost instant gratification and (relatively) instant money as a non-fiction writer, or lumberjack or whatever. With fiction, the pay-off is generally slow in coming even if you write something good. (I know, I know: what about the author of Fifty Shades of Grey?) Even if a publisher decides to pick it up, it can be years before it sees print. And then it might not sell. In the meantime, writing fiction is a lonely business, one viewed with considerable suspicion by your peers. (Unless of course you are already established and rolling in money, in which case it seems quite sensible to everyone.)

Concentrating on non-fiction allows you to see the product in print within a reasonably finite time-span. People are actually reading what you write, and you get to enjoy a certain recognition. You get invited to cocktail parties; you are offered freebies in hotels. You get to go on cruises. More importantly, perhaps, the money normally follows within months at the outside, and you get to eat. In submitting to the demands of the Muse, on the other hand, you flirt with divorce, starvation, unless you’re of independent financial means, and, to outward appearances at least, a thoroughly boring existence.

But what precisely would a book about yours truly be about? Not the life, since no writer really has a life unless, in the American manner, he succumbs to block and becomes a dipsomaniac.

– Anthony Burgess, talking about his first British biography.

In this regard I can refer you to one of my writerly occupational hazards: “Ersatz creativity ” (And here’s a way to exercise “discipline” in face of the Internet, another occupational hazard: “Some good things to do with an Internet addiction.”)

I’ll conclude with a few tips.

What the Muse likes:

- Demonstrations of blind faith and commitment, no matter how fickle she may appear at times.

- Some attention before sleep in the evening.

- Availability first thing in the morning.

- Shared experiences (books, people, interpreting things in light of your project).

- Trinkets, little gifts (in lieu of chocolates, try presenting files of notes to draw upon from time to time, just by way of priming the pump).

The dominatrix muse is adapted, with apologies to artlovers everywhere, from “A Flying Muse, with Harp” (Tate Gallery, 19th century, British School).

A version of “The Muse wears black leather” appeared in the Bulletin of the Foreign Correspondents Club of Thailand (FCCT) some years ago.

Lana Willocks: Really great read, Collin. Thanks for posting! Saving this one for those days when I’m in need of some serious flogging

8 hours ago · Like

Collin Piprell: Thanks, Lana. I was afraid it might sound silly, at least to the uninitiated.

a few seconds ago · Like

Collin Piprell

New rules for seducing the Muse. I’ve cranked up the air-con, donned Blues Brothers shades, and have the music from Sleepless in Seattle playing, all of which should suffice to reproduce the SAD effect on a sunny winter’s morning in Bangkok and thereby grease the creative wheels.

The Longest Nights

opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com

Gray skies and short days are conducive to creativity, or, in any event, to work.

Like · · Share · 34 minutes ago ·

Malcolm Charles Schaverien

Now create a bottle of whiskey hangover, take a laxative, and flush 5,000 baht down the toilet. You’ll feel like you were really here.

21 minutes ago via mobile · Like · 1

Collin Piprell

Wow. That should help. Thanks.

18 minutes ago · Like