Last week we met Mu and learned the key to her libido. This week we meet all of her household, including a distinctive rhythm section and Mu’s sister, Bia.

Selections from Arno Petty’s Intelligencer and Weekly Gleaner

- ALL FOR ONE, AND ONE FOR ALL. Western men have been known to misconstrue what is happening when they marry a Thai lady. Suddenly, as often as not, they discover that there are two cousins from upcountry who need a place to stay while in the city, two sisters and a nephew who have educational requirements entailing money, not to mention one uncle and a great-aunt who are both sick and who need expensive operations before next week. A typical reaction is to decide you are being victimized. Not so. Not usually, anyway. In fact, in this society when you marry you take responsibility for the whole extended family, which with some of these families is a very extensive crowd of people indeed. But it works both ways. When you’re in need the help is there, no questions asked.

- BOOMING BUSINESS. Pirate music tapes are big business, hereabouts. All those vendors blasting us with their samples up and down the streets are franchised by ‘influential people,’ not to say ‘dark forces.’ And it’s funny: when public officials occasionally get it into their heads that maybe this country should start honoring the international conventions on intellectual property and copyright in this regard, some of those same officials start to experience very bad runs of luck, coming up with broken limbs or sometimes even hand-grenades on the back porch.

It seemed strange; everything was normal when I got to my little street only a short time before you found me in bed with Mu’s panties on my head. The truth was, I was just as happy to be alive as not, and maybe more so. I appreciated the songs of the birds and the shouts of the children playing in the road. The late sun slanting through the fronds of the coconut palms on the other side of the temple wall, furthermore, cheered me no end. I could even just about ignore the construction cranes looming everywhere high on the horizon and the thumping of the bass from the tape vendor down the lane.

Everything was more vivid than usual, a shade more real around the edges. I was thinking that if I could talk to Mu, maybe go to bed with her and lie around for a while, then I would feel better still. Because to tell the truth I was feeling somewhat edgy no matter how much the sun was slanting and how many happy children were playing.

The tiny, twisting alley that led to my apartment might have let two thin people pass. The boardwalk was only three planks wide. At the mouth of this alley there was a vendor with a cart, a two-wheeled wooden cart with a glassed-in box full of vegetables and stuff. This was Big Lek the somtam lady, who made green papaya salad with poo, little fermented black crabs, or even without these critters if you weren’t in the mood for gastroenteritis. Mu always said the somtam poo was good for her figure.

Big Lek liked to speak Thai to me, since I was probably the only farang she had ever met who spoke any Thai at all. Only she seemed to reckon if I spoke some I had to speak the whole shtick, philosophical excurses and all, at least judging by the complexity of the raps she laid upon me at times. While she was talking, she would slice and shred papaya and tomato and lime, and she would pound chilies and garlic and so forth in a stone mortar, her forearms big and swollen like a construction worker’s. She gabbled away like a 45-rpm somtam lady stuck on 78, and I never got more than ten percent of it even on a good day.

Right at that moment what I mainly understood was that Mu was home already, my beautiful girlfriend, suay jangleuy. The somtam lady had seen her go down the alley an hour before; when were we going to get married?

I couldn’t shake this feeling of weirdness — here I was with a gut-shot typewriter, it was lucky it was not me instead, and here this lady was rabbiting on just like nothing was amiss, giving me the idea furthermore it was still possible to marry Mu if I wasn’t careful. I showed the lady where the 11mm slug had ricocheted off my typewriter, and I tried to tell her, “Khon mai dee, bad men, song khon, two of them on a motorcycle, kheun motosai, and bang bang, you know? Chai na krap? They try to blow my jesus head off. Taay laeow.”

“Chai, chai,” she told me. “Yes. Motosai mai dee. Too much noise. Motorcycle no good. Chai.” And she grinned at me fondly; it was so nice to have this tame farang to talk Thai to.

You have a day like that — getting yourself shot at, getting to chat to a gang of policemen, getting driven around town by an ancient kamikaze pilot who not only takes ten years off your life but also shakes you down for an extra 500 baht so even if he can’t plug the bullet-holes in his cab he can get his license back. You do all that and you never even get around to flogging your typewriter, which is actually all you had in mind in the first place, except for hitting happy hour at Shaky Jake’s, which you never get to do either; and you think it’s nice to get home and relax — to drop this typewriter some place, your arms feel like they’re going to fall off if you have to carry the machine another step.

Two grinning urchins were sitting in a pile of pink and purple orchids on the landing outside the door to my apartment. They were responsible for the manufacture of these modern improvements on nature, deftly twisting and turning bits of crepe paper into flowers that never wilted, only gathered dust and hung around forever depressing people. I didn’t recognize these two craftsmen, and I guessed they didn’t know who I was either, even though I was the master of the house, because they said “Farang! Farang!” with some excitement and tried to sell me paper orchids. “You! You!” They told me. “Ten baht!” I had to step over them to get at the door.

The door was bolted, as usual; and as usual when I hammered on the door I heard sudden silence followed by mysterious scurryings and rustlings from inside. The flower children on the landing hollered “Farang, farang!” some more, and then the door opened a crack to reveal a girl who brushed her hair away from her eyes so she could see me, and I recognized Mu’s sister Bia, who also recognized me, which was nice, and she let me in.

In Thai bia means “beer,” and Mu’s sister was named Bia because Mu’s papa generally drank whiskey except for one night — chances are the same night Bia was conceived — when for a change he was drinking beer. I noticed she was wearing one of my shirts again, three times too big for her and the shirttails hanging out. I wished she wouldn’t wear my shirts all the time.

The door didn’t open wide, even after it was unbolted and the chains dropped, so I had to sidle in. There were large bundles of sugar cane stacked up against the wall, which explained why the door didn’t open all the way. Sugar cane. I didn’t even ask. Bia told me Mu was having a shower. Then she stood there looking at me. At least I figured she was looking at me. Bia grew her bangs down so you couldn’t see her eyes. And no matter what she said, she couldn’t see a thing with her hair that way, with the consequence she was always tripping over things or falling down the stairs. She thought she had little eyes, which as any Thai lady will tell you aren’t suay, they aren’t beautiful, so she grew her hair down over them and saved her money for an operation. I told Mu her sister would never live to get round eyes, at the rate she was going, and there was nothing wrong with her eyes anyway, except of course they were covered with hair. If she had any money she should get an operation on her brain, which might in fact be defective. But Mu told me I didn’t understand Thai girls. Which was not news to me.

Bia asked me would I like some tea; I said I would like a beer. She turned to go in the general direction of the kitchen and she fell over a stack of wicker baskets. As I helped her up, I noticed bruises on her otherwise lovely legs. Big fresh black and blue splotches overlapping the yellow and blue ones left over from earlier encounters with her environment. I asked her what happened, and she told me she fell down the stairs; it was Mu’s fault. Mu had even got people working out on the stairs now. It was getting so you couldn’t turn around without falling over something, Bia told me. And then she fell over a big box of crepe paper on her way to the kitchen.

There was certainly no shortage of things to fall over in this joint. You looked around, you could find evidence of untold numbers of business enterprises in various stages of realization ranging from “let’s try this sometime” to “that’s the last time we’re ever going to deal in used electric hairdryers.”

These were Mu’s “bisnets.” She had short-term, medium-term, and long-term enterprises of all kinds. Or she used to have, anyway. Her main long-termer had been the box of fish. “What the hell is this?” I had asked, when first I encountered it. “This is a box of fish,” she told me, though it was really a five-foot aquarium tank that held two golden arowanas that she had paid 8,000 baht apiece for. That’s 16,000 baht, and these specimens were each about the size of a good baitfish. This was only 160 Camembert cheeses, as I pointed out to her; 320 large bottles of Kloster beer, and she had spent this sum on two fish? Yes, she told me, plus 1,500 baht for the tank and another 1,000 baht for various pieces of furniture to make the fish happy, since these were not your run-of-the-mill fish, and they should of course have the best facilities we could provide. The idea was that after some time, like about seventy-five years, these prize fish would be worth a total of 200,000 baht. And who knows, maybe Mu was right, except that Mu’s cousin Sombat fed them Mekhong whiskey one night, only trying to be friendly, and they starting floating belly up till finally Mu had to admit they were dead. Sombat to this day is probably the least favorite cousin of them all. Those fish never got big enough to qualify as lunch, much less as a retirement plan.

The fish box was now a showcase for stacks of Dayglo bathing suits, which turned out to have a high turnover in the short term, and which furthermore didn’t go around floating belly-up when you poured whiskey on them, something Sombat was not likely to do in any case, having learned his lesson once.

I have already talked about the sugar cane and wicker baskets, not to mention the paper-flower factory out on the landing. Then you also had the coils of rope that Cousin Rhot braided and knotted up into horses, tigers, deer, people — you name it. He wasn’t around right then, but over by the coils of rope I saw an almost completed dragon three feet long, incredibly detailed, life-like, even though it was only knotted out of plain hemp rope.

There was quite a bit of rope around, but that was nothing compared to the clothes. There were clothes in boxes, clothes on racks, and clothes draped on the sofa. There were clothes everywhere you looked. These clothes came in a variety of electric colors and designs that kind of shrieked at you, if you stumbled across them on a bad morning. There were dresses and shirts, trousers and shorts, even a collection of neckties, over on the bookcase, which would have made excellent gifts for everybody you ever hated.

There was also food. I walked into the next room and found tubs full of vegetables, bags and boards full of meat, bunches of aromatic herbs hanging about, fruit in baskets. Some of this was simply on hand to feed the hordes of relatives, neighbors, waifs, and other assorted hangers-on that Mu liked to keep about the place. And me, of course. The rest of this stuff went towards a variety of bisnet ventures, such as the satay wagon Cousin Lek trundled around the neighborhood every evening, selling tasty sticks of grilled pork with peanut sauce. That was Little Lek, I’m talking about. Big Lek, on the other hand, you have already met. She was the somtam lady out on our lane; for all I know she was also a cousin. (Lek means “little” in Thai, and Big Lek was probably little some time in the past, back when she got her name.) And there was more, only I could never keep it straight, who was doing what, or even who was who and what was what.

I guessed that was why my brand-new computer was already pressed into service keeping account of Mu’s many business interests. My computer. Nobody seemed to realize this was my bread and butter; this was how I made my living. I had only just moved the machine in and already, if Mu wasn’t doing her accounts on it, then Bia was in the bedroom practicing her touch-typing or having Cousin Maem teach her about spreadsheets. Mu said it was no problem; when I wanted to write, I could write. “Bisnet was bisnet,” in the meantime, and why couldn’t she use the computer when I wasn’t there? She was right — there was no reason, none I could think of that held water.

Though I did suspect Bia was spending too much time in our bedroom, and she wouldn’t leave off wearing my shirts. But this I didn’t mention to Mu because I was not sure myself what it signified.

Anyway, when you got tired of stumbling over business enterprises, there were lots of people to fall over instead. These diverse and interesting folk kept things from getting boring, it is true, though I came to feel I wouldn’t mind a little boredom now and then. But Mu would tell me all this was the Thai Way, and she was probably right, since she was the expert on the Thai Way in this house.

*

When Mu came out of the shower, she was wearing a loose shift tied up behind her neck, the bright cotton print clinging appetizingly to her body, her hair glistening wet and smelling of herbs. She was the reason I put up with the rest of it, the stuff that went on around here.

“Jack,” she said, she didn’t even tell me howdy. “What is this typewriter doing here? I thought you were going to sell it.” So the first thing she noticed was another marketable commodity sitting on the floor beside the sugar cane. Most people wouldn’t have noticed the Brooklyn Bridge if you parked it in the middle of this chaos.

“Mu,” I said, figuring it was best to get straight to the bad news, and not beat around the bush. “Listen. Somebody is trying to kill me. And they ruined my best pipe, the Italian one with the big bowl. They shot the goddamned thing.”

“Your pipe? You’re smoking again? You tell me tobacco is too expensive, you’re never going to smoke again.”

“Mu, they were shooting at me. Trying to kill me. They blasted my typewriter, for Christ’s sake. They filled the taxi full of holes as well. And they got my pipe. The Italian one.”

“What? Your typewriter? They shot your typewriter? Is it okay?” She took to rubbing at the smears of lead on the undercarriage, where I showed her. “It still works okay; you can still get a good price for it?” Mu may have been a hard-headed businesswoman, everybody said she was, but I never doubted her basic concern for me, which was why I was still with her, never mind we were going to wind up married if I wasn’t careful.

“Mu, it’s me they were trying to shoot.” I could hear impatience in my voice, which told me I was under some strain.

“You? Somebody try to kill you? Oh, my darling! Who?” Now she was running her hands over me, searching everywhere probably for more smears of lead.

This was a good question. The only person I could think of off-hand who might have wanted me dead was Mu, if only she ever found out where I was that night I told her I was doing some research for a story on Celadon ceramics. Even though I never saw sweet little Ann again, and I had sworn to myself not to screw around any more; I was living with a fine woman and I owed her something even if we never did get married. “Mu, I don’t know who wants me dead. Maybe it was a mistake; they probably took me for some other guy.”

Mu got thoughtful and right away after that she looked more than a bit anxious. “The police!” she said. “What about the police; are they coming here?”

I guess she was worried that they might want a piece of the action when they saw all the business interests she had going in the joint. But I told her to relax. The cops were finished with me for the time being, and probably for ever, if I read correctly their interest in murdered farangs with too many visa runs in their passports.

“Tell me again,” she said. “These two men, they shot at you? With bullets?”

What kind of shooting was it with no bullets? I wanted to ask. But then Mu sometimes had trouble with English, and God knows my Thai was no great shakes. Mu was no doubt distraught, besides, and not entirely sure of what she was saying. Nevertheless, she was reacting in a strange way, I thought. She seemed more angry than worried. You got the feeling if Mu had these inconsiderate types at hand, she would have given them a piece of her mind.

“It was only one man who shot at me,” I told Mu. “The other one was driving the motorcycle.”

“Did they say anything?” Mu was finally getting around to looking worried, I was pleased to see.

“Sure. They said ‘You! You!’”

“Jack. Serious. Did they say anything?”

“No.”

In fact I was thinking this was funny — whoever paid these jokers to take a shot at me was not getting his money’s worth; I didn’t even know why I was getting shot or who was concerned enough to arrange this little matter. Personally, if I wanted somebody dead badly enough to set it up, I would want the guy to know what was what.

“Maybe it was only my typewriter they were after.”

“Oh, Jack; please listen to me. I tell you and I tell you again: you have to be careful. You are too jai rawn, too hot tempered. You can’t do what you do in Thailand; this is not America. You don’t understand. You will get into big trouble one day, if you are not careful.”

This was not big trouble I was in already?

But sometimes Mu seemed to think I went around deliberately trying to get us all in hot water, what with writing about subjects I had no knowledge of and furthermore never listening to her advice. “I told you, you have to be careful who you write about in your newspapers. This is Thailand. You can’t just say anything you like. You have to think about people’s face.”

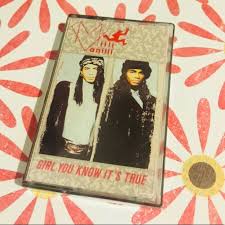

And the week before Mu got so angry with me, she threatened to leave. This was only because I had a slight altercation with the bozo who set up to sell music tapes in the lane outside our building. It was the usual thing — a big wooden table and a tape-deck with two fifty-megaton speakers so the vendor could play samples from daybreak till after sundown. Usually he played a variety of rock’n’roll, both Thai and Western, but this one week he was blown away by Milli Vanilli, and he played Milli Vanilli over and over and over till everybody for 500 yards around could appreciate the finer points of these artistes and all the stray dogs had long since left for some place they could have a quiet nap of a hot summer’s afternoon.

Don’t think I was not impressed with this public servant’s resolve to provide the neighborhood with nice music all day, and for free; but sometimes I had problems concentrating as it was, working at home and with deadlines to meet. So maybe I could be excused if only once I went down to complain, to explain to this goof I was tired of Milli Vanilli, and I was tired of him and tape vendors in general; it was probably best he move his operations to some other venue while he was still intact enough he could move; and so on. I was as persuasive as could be, and smiled a lot, and finally even helped him start to move his stock off the table. Being in a hurry, I just kind of turned the table over, seeing as how we were having trouble communicating; he couldn’t seem to get it through his head that this was now a Tape-vendor-free Zone. There were some hot words, finally, and a gang of interested citizens gathered to attend the debate, which I finally won, since the vendor and some buddy with a pick-up truck eventually moved everything away.

When Mu heard about this discussion I had, she was so upset I wound up giving her a lecture on how to stay cool. “Jai yen yen. Cool, cool,” I reminded her, which got her even more steamed up. Anyway, she couldn’t understand why I didn’t want to have to listen to somebody else’s music all day long every day. If you could believe her, she had never noticed the tape vendor till I started this hassle.

Another thing I freely admit I don’t understand about the Thai Way, is the way everybody thrives on deafening levels of noise, the louder the better, preferably coming from as many different sources as possible. In the restaurants and nightclubs, on the streets, at temple fairs — wherever you go it’s the same thing. Your average visitor to Bangkok asks you how people can stand the constant noise of the traffic, the screaming tuk-tuks, the motorcycles with their mufflers off, the tape-vendors every fifty yards along every street. What they don’t understand is that this is just the background — if a Thai is really enjoying life, they’ll see to it there’s lots more noise than that.

Then there was the noise in my apartment, where I wrote my stories and had trouble even with no noise trying to communicate with Mu and Co. A real estate agent might have called this the “ambient noise,” only a real-estate agent would never have mentioned this ambience unless he absolutely had to.

While Mu was trying to get to the bottom of this latest tomfoolery of mine — this going around getting shot at — Thai pop music was coming from a bedroom; I didn’t know who was in there. Some Western rock group was meanwhile screaming at each other on little Jit’s tapedeck. Jit — I didn’t know for sure how he fit into the scheme of things, probably he was another cousin — was asleep on the floor beside the tapedeck. Cousin Noi was pounding spices in a big stone mortar and singing a broken-hearted Thai love song that had nothing to do with the radio song, the rock piece, or the music leaking into the joint from the new tape vendor out in the lane, the one who set up shop just two days after the last one had left. This music-lover had no Milli Vanilli, and so far I was maintaining the old jai yen, a “cool heart” to make Mu proud, even if I knew some day soon I would kill the son of a bitch.

Noi was going pok-pok-pok with her big mortar and pestle, jamming away with Cousin Daeng, who was going chop-chop-chop with a cleaver, cutting up some meat on a board in the kitchen. Keeow, a roly-poly thing with dimples — I wasn’t sure if she was a cousin or not — made up the rest of the rhythm section, pumping the treadle on her ancient sewing machine as she took up the hems of three gross of sundresses Mu acquired had two seasons before, and which, she had decided, would now sell better if they were four inches shorter.

As if all this wasn’t interesting enough already, you had Bia falling down at more or less regular intervals, and Granny, who was deaf as a post, hollering “Arai na? What? Arai na?” trying to clarify what everybody was saying to her, even when most of the time nobody was saying anything at all to her. Granny was stabbing skewers through pieces of pork for Little Lek and glaring at everybody, especially me, whom she wouldn’t understand even if she could hear anything. And, finally, there was Cousin Dok, who was a katoey, a transvestite. He was practicing being a girl, as usual, by shrieking away in a falsetto and flapping about batting his eyelids till you might have thought he was having an epileptic fit. He was also saving up for an operation, he said, though his was going to cost a lot more than Bia’s. They could have both gone to the same brain surgeon, for my money, and got a two-for-one special.

Dok was shrieking and simpering at Mu’s cousin Meow the Hairdresser, who was laughing and shrieking right back. This was what Thai girls call having a good chat. Meow yelled something at Bia, who then fell over Cousin Sombat, who woke up and yelled at her for her thoughtlessness; he had to get his rest, since soon he would be going to work in Saudi Arabia which, as anybody would have told you, was enough to make you tired. Sombat had already been going to go to Saudi Arabia for two months, at that point. Ever since I fronted him the 1,300 dollars he needed to pay his job sponsor. Once in a while I asked why he didn’t go to Saudi Arabia, now that I had come up with this money, at no small inconvenience to myself, I might have added, but nobody really explained it.

“Wait,” they told me. “We must wait.”

So if you’re starting to get the idea I lived in Bedlam, you’re just about right. Only it was worse than that. It was enough to make you tired even if you weren’t almost shot to death, and more than somewhat worried on that account. All I wanted to do was talk to Mu and get her to give me a massage and tell me everything was going to be okay. And so on. But it wasn’t always easy to get a little privacy. It was enough to make you edgy.

And all Mu could tell me was this was the Thai Way, and I had to “adjust myself.” It was because I was not adjusting myself successfully, I had to understand, that people were shooting at me, and things would only get worse if I didn’t wise up.

On top of that, I couldn’t even smoke in my own apartment. Granny had problems with asthma, though how her lungs differentiated between normal Bangkok air and tobacco smoke I didn’t know.

That night, after I gave Mu the surprise in my shorts, I tried to take the edge off things some more by having a few drinks with Cousin Sombat and Cousin Dok. The ladies, even Mu, kept a steady stream of tasty snacks coming from the kitchen, lots of crunchy-hot-salty-sour stuff that kept you wanting more cold drink no matter how much cold drink you had already, while Bia, sweet thing, kept our glasses full no matter how often she walked into things and fell down till the floor was awash in Mekhong soda. She fell against me at least twice, I had to notice.

Dok worked at his fluttering and shrieking but seemed to get more masculine the drunker he got, while Sombat talked about the things he was going to do with all the money from Saudi Arabia, only he still couldn’t tell me when he was going to go away and get this money. Then everybody sang songs in Thai, except for me, who just made noises in rough approximation to these popular tunes.

Mu finally threw us out, and half a dozen of us went to the club down the road. There we drank some more and I smoked even though I’d quit; and we got to listen to an endless series of Thai ladies climb on stage in party dresses and try to make louder noises than the electric organ and drum machine. Eventually they took off all their clothes and walked around kissing members of the audience instead, which was aesthetically more pleasing than their singing, but which as it turned out cost twenty baht a throw. Dok spent more than Sombat and me put together; you figure it out.

In the morning, I could see that getting shot dead might not have been a bad move, the way I first thought. And Mu expressed some sentiments along the same lines, especially after I screamed at Granny, “Nothing! Nothing. Jesus Christ, oh dearie me. Nobody said anything.”

I didn’t mean to scream at her.

The best thing I could do, I thought, was go downtown and talk to Hippolyte. Maybe he could tell me what was what. And what to do. I was getting really edgy.

.

Next week Jack experiences impromptu hangover therapy on his way to Shaky Jake’s to get expert advice regarding his current situation.